Scuole were religious confraternities. They existed for the purposes of religious self-improvement, charitable deeds, and general fellowship. Scuole grandi were large all-male confraternities whose memberships were drawn from the upper and middle classes across the entire city. There were six of these by the end of the sixteenth century, and a seventh was added in the seventeenth century. The original four (San Marco, San Giovanni Evangelista, Carita, and Misericordia) were created in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries from scuole di battuti, or confraternities that had incorporated self-flagellation as part of their regime. The others (San Teodoro, San Rocco, and, in the seventeenth century, the Carmini) were raised up by the city government from scuola piccolo status. Scuole piccoli were more likely to have a membership limited to a particular parish or ethnic descent, or to a given trade or guild; they also sometimes were either all-female or of mixed sex. All the scuole, but particularly the scuole grandi, were involved in public processions both on specifically religious occasions and also as part of civic celebrations.

All the scuole, whether grande or piccolo, had meeting places. Sometimes these were churches, but more often (always in the case of the scuole grandi) there were separate buildings, which would frequently be adjacent to a church, monastery or convent.

|

|

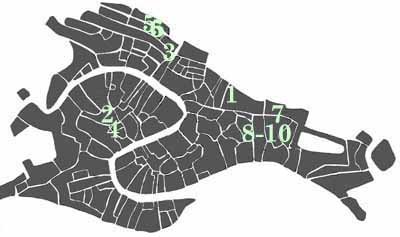

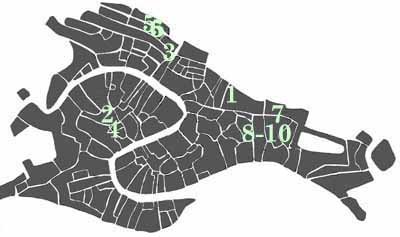

1. Scuole Grande di San Marco, Castello

2. Scuola Grande di San Giovanni Evangelista, San Polo

3. Scuola Grande della Misericordia, Cannaregio

4. Scuola Grande di San Rocco, San Polo

5. Scuola dei Mercanti, Madonna dell'Orto, Cannaregio

6. Scuola dei Mercanti, Madonna dell'Orto, Cannaregio

7. Scuole di San Pasquale Baylon, at San Francesco della Vigna, Castello

8. Scuola of San Giorgio degli Schiavone, Castello

9. Scuola of San Giorgio degli Schiavone, Castello

10. Scuola of San Giorgio degli Schiavone, Castello

|

|

|

|

|

1. Scuole Grande di San Marco, Castello

This was one of the largest and wealthiest of the scuole grandi. Many scuole were located adjacent, but at right angles to an associated church. San Marco is next to one of the two very large conventual churches erected in Venice by mendicant orders: in this case S. Zanipolo, the affectionate Venetian name for S.S. Giovanni e Paolo. It was designed by Pietro Lombardo and completed by Mauro Coducci toward the end of the fifteenth century. On either side of each of the two entryways is a perspectival relief sculpture from the school of Pietro Lombardo.

|

|  |

|

|

|

2. Scuola Grande di San Giovanni Evangelista, San Polo

This scuola grandewas established in quarters that had formerly been a home for the elderly. As a result, the building is L-shaped. Toward the end of the fifteenth century, the scuola commissioned an elaborate screen enclosure from Pietro Lombardo for the space between the confraternity's building and the church at left.

|

|

|

3. Scuola Grande della Misericordia, Cannaregio

The Misericordia is a little unusual in that it was not attached to a church; this vast brick building, begun by Jacopo Sansovino but never entirely completed, was built on the other side of the Rio della Sensa from the original quarters. Unlike the rest of the scuole grandi, it has not been restored; after a career as a sports palace, it is now defunct.

|

|

|

|

|

|

4. Scuola Grande di San Rocco, San Polo

This was another very wealthy and artistically competitive confraternity. The orignal headquarters less than half a mile away were considerably less elegant and imposing; this building, built over most of the sixteenth century under a varied succession of architects, is decorated upstairs and down by Tintoretto. The scuola is separated from its adjacent church by a well-traveled calle.

|

|

|

5. Scuola dei Mercanti, Madonna dell'Orto, Cannaregio

Other scuole were generally smaller and less elaborate. This building, attached to the church of Maddonna dell'Orto, is a typical example, although with an impeccable architectural pedigree: it was rebuilt in the 1570's by Palladio.

|

|

|

|

|

|

6. Scuola dei Mercanti, Entry sculpture, Cannaregio

This building, which housed a confraternity dedicated to merchants, has an extra artistic claim to fame: the sculpture of the Madonna della Misericordia over the entry way, dating from the 14th century, when the building housed the Scuola di S. Cristoforo.

|

|

|

7. Scuole di San Pasquale Baylon, at San Francesco della Vigna, entry detail, Castello

Not all sculptural details are totally cheery--this was intended as a reminder of what awaits us all.

|

|  |

|

|

|

8. Scuola of San Giorgio degli Schiavone, upper facade, Castello

This scuola, still extant but now run by the Knights of Malta, was for persons of Dalmatian descent. Their patron saint is St. George of dragon-slaying fame, and so much of their art depicts his exploits. His most famous deed is featured in this sculpture over the entryway. Inside, there is a famous painted sequence by Carpaccio, showing events in the lives of Sts. George, Jerome and Trifon.

|

|

|

9. Scuola of San Giorgio degli Schiavone, detail of upper facade, Castello

While the relief of St. George dates from the mid-16th century, it is surmounted by a relief of Sts. John the Baptist and Catherine that dates from the mid-14th century.

|

|  |

|

|

|

10. Scuola of San Giorgio degli Schiavone, entry detail, Castello

Sometimes it's the little details that are the most unusual. Sea monsters or whales frolic above the lintel.

|

|